Botulism is caused by toxins produced by a bacteria called Clostridium botulinum. You might know its cousin tetanus. This family of bacteria produce potent toxins that kill animals quickly. Botulism toxin is the most potent toxin known to man. The dose of botulism that could kill a human is about 30 nanograms. That’s 0.000000003 grams or 0.000000006 of a teaspoon! Clostridium botulinum, like other clostridials, is free-living in the soil. Exposure in horses is uncommon and usually through ingestion of the toxin from feed.

The most common form of exposure to botulism toxin is through ingestion. Horses may ingest botulism toxins through eating spoiled hay or hay with a carcass in it. It is possible that any hay can be contaminated, however round bales and baleage are implicated more commonly. Probably because round bales are fed free choice and not monitored as closely as square bales.

Symptoms of botulism poisoning are progressive weakness and paralysis. The toxin affects the neuromuscular junctions, meaning where the nerves attach to individual muscle fibers. The toxin binds to the junctions and prevents impulse transmission. With no impulses passing from nerve to muscle fiber, the fiber becomes flaccid. Symptoms may start with a mild gait abnormality and progress to overall weakness and finally recumbency. As the various muscles become paralyzed the affected animal cannot rise, will have difficult eating and eventually will suffocate due to paralysis of the respiratory muscles.

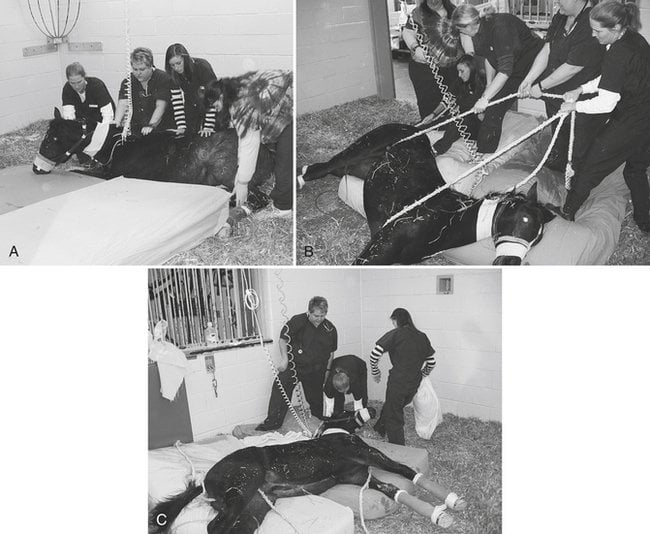

Recumbent horse in hospital

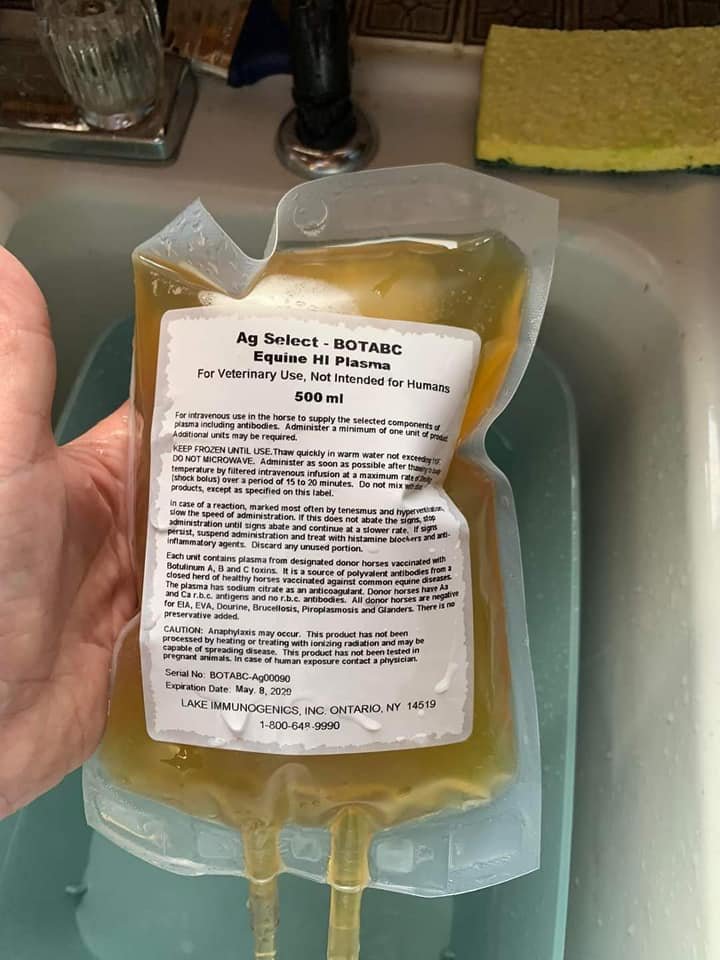

Treatment for botulism should begin as soon as this disease is identified. Unfortunately, there is no clear test for botulism, so often we must rule out other neurologic diseases first. The treatment for botulism is to provide the antitoxin and supportive care. The antitoxin is provided as equine plasma from horses that have been vaccinated for botulism. Equine plasma is expensive! Often a single dose is $1000. Additionally, the antitoxin only binds and eliminates circulating toxin. The toxin that is already bound to neuromuscular junctions must degrade over time. This means that antitoxin administration often will not cause a horse to get better immediately, it just prevents the patient from getting worse. It takes 10 days or so for neuromuscular junctions to regenerate. Therefore, in a horse that is already recumbent, good nursing care is essential.

Equine plasma from horses vaccinated against botulism

Horses that cannot rise will develop pressure sores, have difficulty with digestion, urinary problems and may develop ulcers of the eye. In addition, horses that cannot rise develop a syndrome known as compartment syndrome. This is caused by the pressure of the weight of the horse on the muscles it is laying on. This pressure causes inflammation and swelling of the muscles, which leads to damage, necrosis and eventually loss of feeling in the muscle. Horses that have been recumbent for as little as 24 hours may not be able to rise again. Supportive care means rolling the horse from side to side every couple hours, providing them with nutrition (usually through nasogastric tube) if they cannot eat and water. Recumbent horses do not have a good prognosis even with antitoxin treatment.

Botulism horses have difficulty eating, and can develop pressure sores.

A recumbent horse being cared for by an entire team of people.

Prevention of botulism poisoning is pretty simple. Forages must be made responsibly to prevent inclusion of carcasses and spoiling. Additionally, forage feeding should be monitored so that spoiled hay can be removed before ingestion. If this is not possible, the botulism vaccine should be considered. The botulism vaccine is available commercially and should be considered for any farm that has had a case of botulism or on farms that feed round bales or baleage to horses. The vaccine requires 3 doses, 30 days apart for horses that have not received the vaccine before. After this, it is a yearly vaccine. This vaccine schedule might seem expensive but the cost is negligible compared to 1 dose of antitoxin or the cost of a horse.

The botulism vaccine is readily available.

Botulism cases are not common. In my 10 years of practice, I have treated about 5 cases or suspect cases. Most do not live. Moon’s case turned out well because her pasture mate became progressively recumbent and was euthanized. When Moon started showing symptoms, it was easier to suspect botulism. Botulism is not spread from horse to horse but both were eating from the same round bales that were sitting out and spoiling in the weather.

As always, a consultation with your veterinarian is best to determine if the botulism vaccine is right for your horses. The risk of botulism is low, but some feeding practices may increase that risk.

Emily Dutton